By North Carolina Farm Bureau President Larry Wooten

The old saying goes that ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’ There is plenty of truth to that, and as one of the largest land-owning groups in the state, farmers understand this maxim better than most.

This bit of wisdom is at the heart, both literally and figuratively, of a dispute that has been bubbling over in western North Carolina communities for several years now, and is beginning to come to a head. It centers on the reintroduction and management of elk on federal land in the Appalachian Mountains.

For a little background on elk in the eastern US, let’s turn to the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF).

“When Europeans came to North America, as many as 10 million elk roamed the U.S. Their numbers proved a plentiful resource that explorers, trappers and settlers depended on for survival. But left unmanaged, unregulated hunting and loss of habitat eventually became too great and elk herds east of the Mississippi disappeared by the late 1800s.”

In 2001, the RMEF partnered with the Great Smoky Mountains National Park to reintroduce elk into the Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina. The goal was to establish a wild population on National Park Service land, similar to elk reintroductions in other states like Kentucky and Tennessee. The new herd gradually multiplied, and by 2008 the National Park Service deemed the project a success. The newly-established elk herd was certainly a great addition to our state’s wildlife resources for the public to enjoy.

Sounds Cool – What’s the Problem?

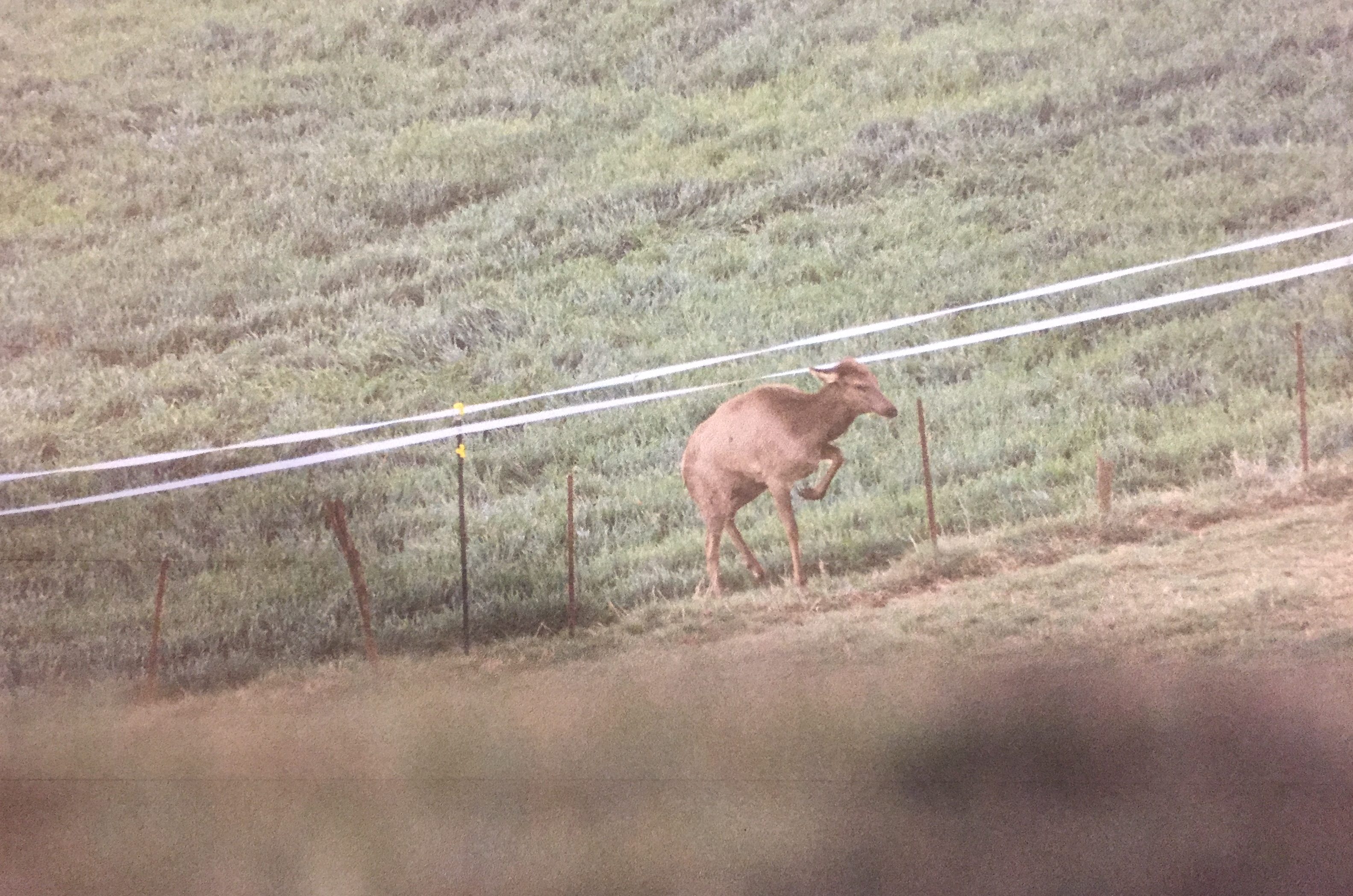

Managing the elk herd has not been without challenges. The population was intended to be managed on National Park Service land with adequate food and shelter habitat to maintain the herd on federal land. Unfortunately, the elk had other ideas. Gordon Myers, Executive Director of the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, explains: “When the first animals were brought in to the North Carolina area of the national park in 2001 and 2002, they stayed primarily in the Cataloochee Valley. As the herd grew over the next decade, the habitat on the park was not sufficient to sustain the larger numbers. Elk will roam over great distances to find adequate feed sources, and often that means migrating to farms and other private property with available forage off of the park service land.”

To the casual observer, a herd of elk wandering into someone’s back yard or onto a farmer’s field may not seem like much of a problem. But from a farmer’s perspective, it can be a big problem. For one, elk can startle livestock and damage the fences that keep them safely in the field; elk also devour crops including grasses and hay that farmers sell or use for feed.

Gordon Myers again: “For farms and businesses that become homesteads for large numbers of elk, the landowner should not be saddled with the economic loss they incur from crops being eaten or fences and other property being destroyed by the herd.”

NC Farm Bureau and others have always raised concerns about introducing wildlife into the state without having a long-term wildlife management strategy. But regardless of how the elk were brought in and who is ultimately responsible for them, they are here to stay. So, too, are farmers and other private landowners.

Some groups and individuals have tried to pick winners and losers in the press, acting as though this is a zero-sum game where only one side can prevail. Name-calling, finger-pointing, threats, and demeaning statements about farmers are not constructive and do nothing to foster an atmosphere for the animal to coexist in today’s landscape. This problem is solvable, but we won’t get there unless we work together.

To begin moving forward, we need to begin having a productive discussion. NC Farm Bureau believes private landowners have a significant and legitimate grievance; at the same time, we want to help with supporting a sustainable elk herd in North Carolina for the public’s enjoyment. We think both of these goals can be accomplished, and believe the public can and does appreciate both sides of this issue.

Finding a Win-Win-Win Solution

So, how do we sustain the elk herd in North Carolina, preserve the wildlife resource for public education and enjoyment, and protect the interests and safety of private landowners? It may be difficult to thread that needle, but it is worth the effort.

First, the animals need reliable sources of food and shelter; when they have both in one area, they tend to concentrate there. Developing these resources on public land should be fully explored, and the National Park Service, US Forest Service, and other agencies are working on this now. They need to step it up a notch.

There may also be opportunities to locate the animals on other tracts of public land, and possibly even on private land where landowners with adequate resources for the elk are willing to support the animals. This could be a short-term strategy to take the pressure off farms and other private landowners, as well as reduce the safety risk to schools and recreational areas where personal injury, especially to children, is heightened.

Relocating the animals, or a portion of the herd, is not without challenges as well. But this option should be strongly considered in the overall approach to sustain the elk population.

We also feel that successful reintroductions in other states might give us some ideas of how to provide adequate habitat for the herd here in North Carolina, fully recognizing our terrain and natural resources may not be exactly the same.

When Fences Don’t Make Good Neighbors

Arriving at this solution is going to take cooperation, communication, and compromise. It may require an outside-the-box, multi-faceted plan with both short- and long-term strategies for success. This is not the time to push away and divide our neighbors into rival factions, but rather to set our differences aside and work towards a solution where everyone wins.

Gordon Myers again: “We are in this together as the first generation of North Carolinians to live with elk on the landscape. We must all work together to find ways to adapt. To protect the elk, the public, and private property, a long-term management strategy is needed among a wide range of partners, including state and federal wildlife officials, the National Park Service, NGO partners such as the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, local government, and private landowners.”

I urge everyone who has an interest in this issue to help with the solution, without drawing lines in the sand that ends up picking winners and losers. The North Carolina elk reintroduction is certainly a great opportunity to show how a challenging wildlife issue can be solved in our state, perhaps even creating a model for future wildlife management strategies here and across the country. North Carolina Farm Bureau wants to be a part of the discussion to solve this problem in any way that works to sustain the elk herd, and at the same time respects private property rights.